A reader writes:

“Hey Nords, are you old enough for Tricare For Life yet?”

“I have been a long time reader of your website and enjoyed the many posts you’ve made. My wife and I are both retired from the military. As we have continued to look into our retirement when the kids finally graduate and leave for college, the part that Medicare plays for our healthcare is somewhat confusing.

I was wondering if you would be able to run an article, or several, into how Medicare plays into the healthcare plans for military retirees. I have spoken to several military retirees and we all have some different ideas as to how or what parts of Medicare we need to sign-up.

Again, depending on several ideas as to coverage for VA 100% permanent disability, or 60% permanent disability, or a retiree who isn’t rated as disabled by the VA and receives their care thru normal TRICARE providers or military treatment facilities.

An additional continuation on this thread would be the use of Medigap plans.

You have had some great articles on the retirement system as far as pay is concerned and this subject would be a great continuation for that. Thanks, M”

Well, M, you’ve waited patiently (for months) on this response, and it’s finally getting real.

Yes, I’m almost there— October 2025 was my 65-years-old milestone.

I’ve gone through my notes collected over my last 25 years of writing about financial independence, and it’s scary how much Medicare info I’ve collected “in case I need it someday.”

“Start here” and…

There’s an earlier critical number that sneaks up on people: age 63. I’ll explain the IRMAA one-year tax trap below.

If you’re of a similar age (or if you’re eligible for Medicare sooner than age 65), then here’s the countdown to yet another financial & medical military milestone.

Your Military Retiree ID Card Can Expire.

If you’re a U.S. military retiree in your 60s, you’re probably aware that you’re going to transition to Tricare For Life as part of becoming eligible for Medicare. This happens for retired Guard & Reserve members as well as for active-duty retirees.

This transition also includes servicemembers who’ve been medically or physically retired on a DoD Chapter 61 disability pension.

What’s not always clear is that retiree ID cards expire on the month before your 65th birthday to force this transition. That expiration is tracked by a couple of my favorite acronyms: the Defense Manpower Data Center in the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System.

Yeah, I know, a few of us woolly mammoths might still have retiree ID cards with “INDEF” on the front in the expiration date block. If you have one of those, then turn it over. Get your magnifying lens and read the tiny print on the back: the “Medical” block will have an “EXP DATE” of the month before you turn age 65.

You don’t want to accidentally let your military retiree ID card expire. That can kill your

– Tricare health insurance at a hospital,

– one of your Real IDs for commercial travel,

– your boarding pass for military Space A travel, and

– your military base access.

You might even have to find a U.S. military ID facility in a foreign country to issue you a new ID card. We don’t have to get into how I learned that but the office in Rota, Spain had great customer service.

Your military ID’s expiration date is also encrypted in its bar code. If the military base’s gate guard puts your ID card under their scanner, then expired IDs can be confiscated.

Fortunately, DMDC is here to help us with a handy notification letter, which showed up in my mailbox long before I was in the window to sign up:

DMDC: “Happy early birthday!”

Keep in mind that this letter is generated from the DEERS database and sent to whatever mailing address you have on file there. If DEERS is accurate then you should be fine. If you’re changing your mailing address during your 64th year, then pay attention to your Medicare transition.

They also e-mailed me this countdown reminder:

“Your Uniformed Services Identification (USID) card expires in 89 days. You are eligible for the online USID card renewal program. Once you submit an online renewal request, your card will arrive via U.S. Mail eliminating the need to visit a RAPIDS ID Card Office.

To make the online renewal request:

1. Go to https://idco.dmdc.osd.mil/idco/

2. Select “Continue” in the Family ID Cards block and Login.

3. Click the “Request ID Card” link underneath your name and complete the request.”

Not having to deal with RAPIDS appointments, the crowds, and the system’s downtime? Priceless.

Caution:

… For Life.

I’ve learned (from years of experience) that writing about Tricare just makes everyone angry.

The people who have it complain about the quality of care and the bureaucracy, while people who don’t have it complain about perceptions of entitlement or a lack of gratitude. Tricare can always get better, yet just about every other form of American health insurance seems worse.

We’re going to try to avoid those Perpetual Internet Debates here, and I’ll stick to the basic 2025 plans & financials. The detailed & complicated rates are linked at Tricare’s comparison page and also on Tricare’s plans page.

If you’re a military veteran who’s not eligible for any military pension, then consider care (and prescriptions) from your local VA clinic, or from Tricare’s Transitional Assistance Management Program, or the Continued Health Care Benefit Program.

Depending on the nature of your separation: one of those programs can help bridge the healthcare gap to your next employer, or an Affordable Care Act marketplace, or Medicare.

If you’re a veteran but not a retiree (not eligible for Tricare For Life) who wants to buy a Medicare supplemental insurance policy, consider this classic blog post by another OG financial independence blogger, John Greaney. Your “20% that Medicare doesn’t cover” could be as small as a few percent of the original bill, and may include a cap.

The other pro tip I’ve learned from social media: do not get suckered into Medicare Advantage supplemental insurance. “Free” is too good to be true, and it will leave you with either denied claims or facing a tremendous coverage hassle. Instead of an Advantage plan then either (depending on your health) pay the cost share of Medicare B (which could be capped and a lot lower than 20% of the quoted cost) or buy a more traditional Medicare supplemental insurance policy.

Tricare For Life (Supplemental Insurance and Medicare Part D)

For military retirees, Tricare For Life acts as both Medicare supplemental insurance and (here’s the best part) Medicare Part D prescription insurance. The second-best part? Tricare For Life currently has no enrollment fees. You can learn more information from this brochure by downloading the eight-page PDF.

However there are still expenses: military retirees have to sign up for both Medicare Parts A&B before starting TFL, and Medicare Part B currently costs $185/month.

One more note about age 65: if you choose to keep working past your enrollment period (for whatever reason) and keep using your employer’s healthcare plan then you might not have to sign up for Medicare. You can read more about the tricky details at that link.

If you’re working past age 65 with employer health insurance and you don’t sign up for Medicare, then you’ll still need to renew your military retiree ID before it expires at age 65. You won’t be eligible for Tricare For Life (because you’re not signed up for Medicare Part B), and you’ll absolutely want to let Tricare know that you’re using your employer health insurance.

IRMAA

Medicare has another surprise fee if you earn a high income or have a big money event: “Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amounts.”

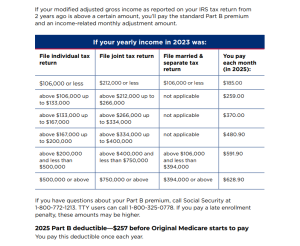

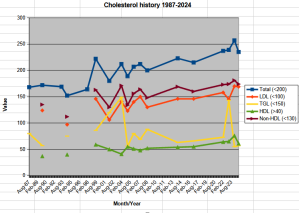

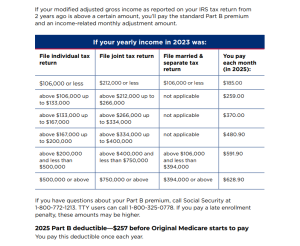

IRMAA 2025 rates

In 2025, IRMAA kicks in when your Modified Adjusted Gross Income exceeds $106K (Single filer) or $212K (Married Filing Jointly). The first tier of IRMAA adds another $74/month to your $185/month Medicare B premiums.

Here’s the age-63 catch: IRMAA for the current year is based on your income-tax returns from two years ago. (It takes that long for the IRS to accept a tax return and transfer the data to Social Security.) And yes, the IRMAA data is reviewed by Social Security before they tell Medicare to add on your IRMAA. This means that your 2025 IRMAA is based on your 2023 MAGI.

The second level of IRMAA adds yet another $111/month.

If there’s any good news about IRMAA, the higher Medicare B premiums only last for a year. If you had a one-time leap in your MAGI (for whatever reason) and it’s not repeated during the following year, then you won’t pay that IRMAA tier again.

“Golly, Nords, I’m a retiree. I won’t trigger IRMAA!”

Well, maybe. Your federal income tax returns include your military pension, any civilian income you (or your spouse) earned, interest income, dividend income, capital gains, net rental-property income, any Roth IRA conversions you might have done that year, … you get the point.

Of course VA disability compensation is tax-exempt and not even reported to the IRS.

If you have some (or all!) of the above income sources and then start receiving Social Security deposits… IRMAA could be part of your Medicare fees each year for the rest of your life. It’s one (more) reason why my spouse and I are delaying our SS deposits until age 70.

If you do end up triggering IRMAA in any year (very much a first-world problem!) then you can file an appeal due to a recent life-changing event:

– marriage,

– divorce,

– death of a spouse,

– unemployment,

– loss of a pension or income-producing property, or

– an employer settlement payment.

Sadly, I can attest that rebalancing your investments (and possibly incurring a bunch of capital gains) is not an exception to IRMAA rules. You can appeal, but you’ll still pay.

If you’re going to make big, bold financial moves (like rebalancing as you get ready to retire, or just one more Roth IRA conversion) then consider doing them before the year you turn 63.

What About Tricare For Life And the VA?

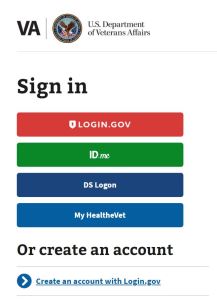

Just Login.gov and ID.me now.

They’re two separate systems, but Tricare For Life and the VA also complement each other.

The VA will care for your service-related conditions and some preventive care like immunizations, hearing aids, and possibly prescriptions, but the VA is not a Medicare-authorized provider. They can’t bill Medicare for your non-service-related medical care.

There are a few benefits that Medicare won’t cover (like hearing aids) but the VA will provide hearing aids when your audiogram justifies them.

Even if you get all of your current medical care from the VA, you’re still strongly encouraged to sign up for Medicare and Tricare For Life.

A final note: As many of you traveling retirees have already learned, Medicare is severely limited when you’re outside of the U.S. In that situation, Tricare For Life becomes the primary coverage.

For those retirees who are traveling or living overseas, I’d recommend John Letaw’s outstanding book “The Ultimate Guide to TRICARE.” You’ll probably pay your overseas medical expenses up front and then file a Tricare claim, but there are lots of exceptions to this general practice.

Signing Up For Medicare

Ironically, you don’t sign up for Medicare at the Medicare website…. you sign up for Medicare at the Social Security website. Sure, wherever.

Click for Medicare signup.

For most eligible adults, the signup window for Medicare begins three months before age 65 and lasts for three months beyond the month of your 65th birthday.

It’s a whole seven months around that birthday, and there’s a few exceptions.

For example, if your birthday is on the first of the month then your window starts earlier: four months before you turn 65 until the end of the second month after the month you turn 65.

Generally, your Medicare coverage starts the first day of the month before you turn 65. Part A (the hospital benefit) starts the month you turn age 65. For those born on the first of the month, your Part A coverage starts the month before you turn age 65. Yay?

If you sign up for Part B before you turn age 65 (because, like me, you don’t want your military retiree ID to expire) then Part B starts during the month you turn age 65. Otherwise it starts the following month, but you’re going to have to renew your military retiree ID to get Tricare For Life.

Even worse, if you turned age 65 before signing up for Medicare, it’s possible that your Tricare insurance lapsed until you renew your military retiree ID and sign up for Tricare For Life.

Using The Social Security Website

In June 2025, Social Security shifted their login requirements to Login(.)gov or ID(.)me. Even if you’re an online dinosaur like me, and you’ve had a mySocialSecurity account for years, you still have to start using Login.gov or ID.me.

I’d like to tell you that I was already aware of this, but… no. I only log into SS once a year to check my benefits estimate, and I missed the press release about the new login system. I found out at the end of June when I paranoid tried to log in to mySocialSecurity to check that I’d be able to sign up for Medicare.

I already had a Login.gov account to log in with the VA for my veteran’s benefits, so I should be able to log into Social Security, too, right?

Not so fast.

The mySocialSecurity account agreed that my Login.gov account was legit, but SSA still needed me to go through the Login.gov verification process all over again. This required photos of my driver’s license and a smartphone selfie, just like trying to renew a passport or sign up for Global Entry. (I’m seeing a trend here.) It took me four attempts, a blank wall with a plain white background, and 45 minutes. No, I’m not going to show you my grumpy face on the fourth headshot attempt.

On the third failure, the Login.gov site helpfully suggested that iPhone users should use the Safari browser. (Well, I was using Chrome. Bummer.) I started all over again with Safari and the Login.gov system finally accepted my headshot– but it still couldn’t read the bar code on my driver’s license. The good news is that it could read the rest of the license and it (finally!) had the info it needed for me to finish the verification.

Based on my birthday, my three-month signup window opened in July. After the holiday weekend (just in case there was heavy website traffic in early July), I returned on 7 July to git ‘er done. This time the login to MySSA went smoothly.

I chose “Medicare ONLY without Social Security monthly retirement cash benefits” because I plan to claim SS at age 70. (That choice is a future blog post.) I also chose “No coverage under a Group Health Plan” because I don’t have an employer plan.

In an abundance of excess caution, I explained myself in the Remarks section of the application:

“I’m a U.S. Navy retiree (retired from active duty) who wants to sign up for Medicare A&B in order to become eligible for Tricare For Life when I’m eligible for Medicare.”

The next day the SSA.gov website e-mailed me:

“Thank you for filing your Social Security application online. Our Social Security Office in SALINAS, CA received your claim and will be working with you to process it.”

The card is in the mail!

It tuns out that they meant to write: “Thank you for filing your *application for Medicare on the* Social Security website.” There are two SS offices on Oahu, and I have no idea why Salinas gets the job. There’s also a link and a phone number for checking the status of the application.

A week later I got a “Notice Of Award” letter confirming that Medicare A&B would start in October.

It also promised that I’d get a Medicare card within two weeks, and that happened right on time.

Card-carryin’ membership.

Setting Up A Medicare Account

Once I had my Medicare number (a randomly-assigned code, not my Social Security Number), I was able to sign up for a Medicare account with EasyPay monthly deductions from my checking account. Interestingly, their website uses one of the largest default fonts I’ve ever encountered– gee whiz, it’s almost as if all of their visitors are wearing presbyopian reading glasses and have trouble focusing on tiny numbers.

Along with setting up my Medicare account and EasyPay, I also told the site that my spouse & our daughter have my permission to act as my representative. (That link downloads the PDF version of the request.) Finally, I set all of Medicare’s correspondence to e-mail instead of paper mail.

A few days later, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services sent me a letter through the postal mail. CMS wanted to make sure the online account had been set up by me (not a scammer or hacker). The letter also gave me the usual list of their site’s services and how to get help with my account. Hopefully that’s the last time they contact me by snail mail.

Setting Up Tricare For Life

Now that I have a Medicare number (and when I’m also age 65) then TFL is supposed to kick in automatically, presumably because Tricare links to the Medicare database.

Here’s what Tricare says about TFL:

“You aren’t required to enroll in TFL.

TFL coverage is automatic if you have Medicare Part A and Part B.

Coverage starts the first day Medicare Part A and Part B are in effect.”

Next Up: The New Military ID Card

Remember how the Defense Manpower Data Center e-mailed me that I could renew my Next Gen retiree ID online?

Well, unfortunately they also e-mailed:

“On May 21st, 2025, the Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC) introduced myAuth, a new login system designed to provide users with an easy and secure way to access DoD online services.

Did you know you can make your myAuth login faster and more secure with the free Okta Verify app? By downloading the Okta Verify to your mobile device, you can use one-click push notifications to authenticate or even set up one-step password free authentication on your mobile device.”

Oh great. *Heavy sigh.*

Before I could download the Okta Verify app, I had to get into my DS Logon account. Before I could do that I had to reactivate the DS account, because a few months before I’d let my password expire.

I finally got back into my DS Logon account and had the myAuth QR code on my desktop PC’s monitor. Then I downloaded the Okta Verify app on my iPad and set that up. I brought my iPad over to the desktop monitor’s QR code and…

When my iPad camera caught the QR code, the Okta app blazed through 3-4 screens too fast for me to read. When it settled down, it said that myAuth was good to go. I’m a tech nerd, and I’d love to know how the iPad and PC zipped through the QR code so quickly, but I’m not going to mess with success.

Next I expected to sign up for a new Next Gen ID card. Or what I hoped to do, anyway.

“What’s The Expiration Date Of My New Military Retiree ID Card?”

After receiving my Medicare card and checking that Tricare West knew I was starting Tricare For Life in October, I wondered how DMDC knew that I’d signed up for Medicare & TFL. If I renewed my ID card by mail, would they give me a new expiration date? Or would it be the same 30 September 2025 expiration date that I have now?

I decided to call their customer-service line.

The customer-service representative claimed: “Some of our sponsors have told me that their mailed ID card had the old expiration date.”

I’m not making that up. Not only did the DMDC call center not have a reference on renewing an ID by mail for Medicare & TFL– they were also repeating gossip from social media.

I eventually got a supervisor, who admitted that they just don’t know how DMDC sets the date on new IDs by mail.

He suggested that if my ID didn’t show up in the mail within 30 days, or if the new ID still had the old expiration date on it, then I could report it lost/stolen and visit a RAPIDS site (in person) to get the proper ID.

I’m still not making this up. These are the customer-service experts giving their best advice. Because, you know, it’s really rare for 64-year-old military retirees to sign up for Next Gen ID cards along with Medicare & TFL. [/snarcasm]

(If you work for DMDC, feel free to contact me with more links.)

You submarine vets are already smirking while reading this, because you already know what I did: I applied for my new military retire ID by mail, and I also made a RAPIDS appointment for 35 days later. If the new ID still had the old date on it, then I’d still have a RAPIDS appointment (with my Medicare card in hand) to get the right date on my military retiree ID.

I logged into that DMDC site on 22 July (once again using the Okta Verify app for a confirmation code) and requested a new military retiree ID. DMDC’s site claimed it would send an ID with an expiration date of INDEF.

Two days later, DMDC e-mailed:

“Your request for the cardholder’s DoD Uniformed Services Identification card (USID) has been successfully processed. The card has been mailed to the cardholder via the U.S. postal service.”

On the 28th, my new ID was in my mailbox. It got to Oahu from Wichita KS in only four days, which is better than average. Kudos to whoever set up that mail-response process with the USPS.

Best of all, my new military retiree Next Gen ID has a large INDEF date on the front. The back of the ID notes an effective date of 2025July22, the date I requested it.

Like a bank card, it was wrapped in a notice that sternly admonished me about the requirement to activate the card before I could use it. The activation not only turns on the card in the various databases but also makes it valid for a military base’s scan by a gate guard.

(I’m also flying to the Mainland in September, and the TSA checkpoint in Honolulu airport will let me know right away if the card works in their system. Just in case, I’m also carrying my passport.)

Once again I logged into the DMDC site (and yes, still yet once again with the Okta Verify app) to confirm that I’d received the card– and then I activated it.

Finally, I canceled my RAPIDS appointment.

“What’s Different On The Military Retiree Next Gen ID?”

(You only care about this section if you’re in your 60s and you’ve carried a laminated paper retired ID for a while.)

The Next Gen ID started rolling out in 2020, perhaps slowed by the pandemic. There are rumors that it’ll be mandatory by January 2026, but nobody has formally announced it yet.

At that last link, DFAS used to list 1 January 2026 (along with DMDC and Military OneSource) but DoD recently walked everybody back to “somewhere during 2026.”

I’ve joked about DD Form 2s for over 45 years: it’s the ancient DoD form number for a military ID, and also the form number for placing U.S. Naval Academy midshipmen on report. Those days are over: I’m now carrying a DDUSID.

It looks more like a bank credit card than a laminated ID. It has a color photo instead of black&white, and I didn’t have to sign it before it was laminated.

The front declares that I’m an authorized patron for MWR benefits, the commissary, and the exchange.

The back is covered in bar codes. It also squeezes in another headshot (with my date of birth), my DoD ID number, my Tricare benefits number, and the date of issue.

The back also states “Medical: Verify Eligibility.” The website for the Common Access Card claims it’s Tricare’s fault:

“… changes to TRICARE that make it extremely difficult to accurately display a cardholder’s medical benefits on the back of the card, such as requiring enrollment within 90 days of a qualifying life event, establishment of an annual open enrollment window, and defaulting to Medical Treatment Facility care only if a TRICARE option was not selected. Medical providers verifying eligibility ensures the appropriate medical benefits are provided to the appropriate populations.”

Frankly, I’m surprised that this cards-by-mail process went as well as it did. My paranoia feels justified, especially the parts where the federal government agencies have been changing and upgrading all of their logins with new security systems. I’m glad I went through my dress-rehearsal logins well in advance and had the time (and patience, and perseverance) to deal with balky hardware & apps.

Although we can easily search for information from Social Security, Medicare, Tricare, and DMDC, it’s an overwhelming stack of reference material with unreliable keyword searches. (It’s also in just about every military retiree newsletter– and even old-skool military retiree magazines.) If you’re not a technically literate website user (or if your cognition is declining in your 60s) then it’s very challenging to navigate all of the decision branches.

If you don’t have a smartphone for the apps then you’re not completing the process online at all. Even worse, if you’re not physically mobile then you absolutely need an advocate to help you get to all of the local offices of the agencies.

This is one of the longer posts I’ve ever written (over 4400 words) and its keywords should keep it on the first page of search results for a few years.

Have you signed up for Medicare & TFL yet? As a notorious television doctor asks: How’s that workin’ for ya?

Please post your other Tricare questions in the comments, or use the Contact me link, or e-mail me at NordsNords at Gmail!

There are no affiliate links or paid ads in this post. Try your military base library or local public library before you pay money for these books– in any format.

Military Financial Independence on Amazon:

Raising Your Money-Savvy Family on Amazon:

|

- Reach your own financial independence

- Teach your kids how to manage their money

- Specific tactics from my adult daughter

- Checklists and spreadsheets for your family

Use this link to order from Amazon.com!

|

Related articles:

Questions About Medicare + Tricare? We Have Answers.

How I Cost My Dad Over $2000 in Medicare Benefits

Medicare, Tricare For Life, Medigap insurance, and Congress

Financial Peace While in the ICU

Why You File Your Veterans Disability Claim (Not Just How)

Updated VA disability claim and medical tests

Medical Tourism at Bangkok’s Bumrungrad Hospital (2025 update)