This post is about living your best life in financial independence… while you still can.

As you veterans know, if we’d realized that we were going to survive our military careers then we would have taken better care of ourselves.

I’ve already posted about the PACT Act to help motivate vets to update their VA disability claims. The “Related articles” section at the bottom of this post has more info about the screening process and why you want to get it done now.

This post is not a cholesterol or a cardiac tutorial. It’s not an organ recital. However it’s very much an explanation of how your aging process can reveal new conditions which might have a presumptive service connection. The PACT Act has greatly simplified the process of claiming those service-related conditions.

The information I’m sharing about my health today could turn into yet another update on my VA disability claim– so that my family doesn’t have to go through it (yet again) when I’m even older.

This post is also a guide to living with potentially life-threatening chronic illness(es) while still making the most of whatever time you (think you) have left. I frequently hear from military families (and some survivors…) about the health issues of older vets. I never thought I’d join this club, but sometimes life comes at you fast.

I’m doing well, and I’m very glad to have fully lived my financial independence during the last 23 years. I might still be a time billionaire, and I hope to use it under my own control for as long as possible. If I’d tried to pursue paid employment into even my 50s (let alone my 64th year), my genome would have amplified the workplace stress to shorten my life.

In the immortal lyrics of that classic-rock composer:

“I can’t complain, but sometimes I still do: life’s been good to me so far.”

— 20th-century philosopher Joseph W. F. Walsh.

Our Story So Far

I turned 60 years old in late 2020, during peak pandemic. I didn’t start catching up on my regular annual checkups until early 2023.

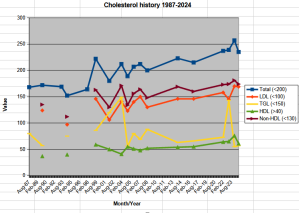

The first piece of unpleasant news in 2023 was my rising cholesterol levels. As my total cholesterol rose above 200 (and my LDL above 150), my family doctor started discussing weight, diet, and lifestyle.

For those who want to really dig into the details, this 2018 report from the American Heart Association lays out the management of risk factors and cholesterol levels for older adults. The American College of Cardiology chimed in with their risk estimator for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: the dreaded ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus.

I’m consulting a great family doctor (with Tricare Select) in our neighborhood. He’s simultaneously experienced enough in this topic to answer my detailed questions… and humble enough to admit that he doesn’t know everything. I might eventually shift over to our new Oahu VA clinic in Kapolei, but I’m happy so far.

Doctors have way more training and proficiency at these discussions than we patients. I’ll take you through the process with my doc, and hopefully you can extract more benefit from talking with yours. Sharing this post with them would be just bonus.

My doctor and I started with the statistical flaw where my risk factors dramatically jumped higher between my last day of age 59 to my first day of age 60.

My lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease (atherosclerosis) rose from 46% to… well, the studies stop estimating lifetime risk at age 59. My optimal 10-year risk at age 59 was already 7.4% (“borderline”) while the statistically optimal risk (of surviving a heart attack in the next decade) for that age group was considered to be 5.2%.

The next day (my 60th birthday) my risk spiked up to 8.1% (“intermediate”) and my optimal 10-year risk was 5.7%.

Having the overall risk spike by half of a percentage is bad enough— and yet mine spiked by 0.7 percentage points. “But I didn’t even do anything?!?”

The 2018 AHA study recommended that I take their actions #7 and #8: a bunch of additional testing, maybe an expensive scan, and a prudent dose of a moderate statin.

But what about side effects? Us 1960s Baby Boomers can remember the 1990s when statins had a bad reputation. And would I have to take them for the rest of my life?!?

I might have accused my doctor of earning an affiliate income from selling statins. He’d heard these protests before, and I think he’s had this talk with way too many people who are in far worse condition than me.

Then I pointed out that at age 60 my chance of not having a heart attack was 91.9% (=100 – 8.1).

He’d heard that before, too. He politely riposted that during the next three decades of my life, 91.9%^3 is 78%, which means the risk of having a heart attack before age 90 (let alone surviving it) had risen to 22%. As Dirty Harry Callahan used to ask the gun-toting criminals: “Do you feel lucky? Do you??”

Even more unfortunately, if I managed to hold my same cholesterol levels to age 70 (despite their steady rise since my 40s), the ACC calculator claimed that my statistical risk during the next decade still rose from 8.1% to 17%. At age 80, it rose to 29.2%. Now the odds of not having a heart attack before age 90 had dropped to 54% (= (.919)x(.83)x(.708)).

In other words, if I did nothing then I’d have at least a 46% chance of a cardiac incident by age 90. That’s probably the equivalent of “hope is not a plan” followed by “game over.”

As a mature and responsible 63-year-old, I pretty much stomped out of the doctor’s office to take another grumpy look at my lifestyle. Then I started reading about cholesterol, and my questions on the Millionaire Money Mentor forum also referred me to Dr. Attia’s book “Outlive.”

I’ll refer to that book during the rest of this post. I didn’t enjoy the read because he tells too many long stories on tangential topics, and some of his analysis is still viewed with skepticism from other doctors. However he knows the research and he explains the vocabulary & mechanics, which I re-read several times. He also presents the same material in his podcasts & videos.

Living My Best Weight-loss Life: Slow Travel

As I learned more about cholesterol and cardiovascular disease, we also made our first long trip since the pandemic: seven weeks in Japan, mostly Tokyo & Kyoto. In between enjoying the country, I plowed through a lot of that Attia book.

During our trip, we walked several miles per day almost every day– even during our down days. It’s also easy to eat healthy there, especially with kitchens in our lodgings. Over that seven weeks I managed to shed six pounds (admittedly some of it was surfing muscle). My body finally broke through some sort of resistance setpoint, or I finally committed to losing the weight. I realized that I could gently boost my activity level in a sustainable way without chronic injuries.

But then during the final week of our trip I contracted the worst case of sinusitis I’d ever had in my life. I limped back home and spent several months getting it under control.

Part of the cure was a CT scan of my sinuses to check for other… issues. (That’s medical tact for “polyps, tumors, or lesions.”) To nobody’s surprise, a couple of my sinuses are permanently scarred. If there’s any good news, it turns out that exposure to volcanic ash (resulting in sinusitis) is related to the PACT Act. This CT scan also facilitated raising my VA disability rating to 40%.

Once my sinuses cleared up, I was finally mentally & emotionally ready to re-engage with my family doctor about cholesterol control.

More Cholesterol Tests

In early 2024, as I learned more about cholesterol and talked with my family doctor, we decided to test my lipoprotein(a) and my apolipoprotein B levels. If you haven’t seen these words before, they’re different ways of assessing how your body handles cholesterol (or doesn’t). They’ve been around for a few years, and they’re probably a better indicator of risk than the traditional cholesterol blood tests, but they’re still gaining acceptance. You can review their history in chapter 7 of Attia’s “Outlive” book.

Those blood tests aren’t offered on Oahu but could be shipped to a California lab, and I’d pay a bit more to Tricare Select. During my sinusitis disability claim update with the VA I learned that my cholesterol numbers meant I could get them tested for free by our local VA clinic, so if you’re facing a statins decision then consider discussing it with your VA clinic too.

My Lp(a) came in at 107, “moderate leaning toward too high.” Since it’s largely based on genetics, it would probably not change even if I dramatically changed my lifestyle. “Good luck!”

ApoB came in at 106, also “moderate leaning toward too high.” This can be lowered with various interventions, which leads directly to a discussion about weight, diet, lifestyle, and… statins.

During the previous year I’d shed at least 10 pounds of fat and returned to a weight last seen in high school. My BMI was back under 25. (Well, at 24.99 and dropping.) I was exercising more regularly (now that the sinus infection was finally at bay) and I rebuilt my surfing muscles. The weight, the diet, and the lifestyle are all part of a process that’s going as well as it’s going to go.

The Lp(a) and ApoB were not the results I was seeking. Dirty Harry was right: I’m not lucky.

Coincidentally, the week after those results came back, a family friend (a retired Marine) had urgent triple bypass cardiac surgery. He’s in his mid-50s and he still exercises like, well, a Marine, but he frequently felt tired during the day and had less stamina.

He went to his local clinic on Friday afternoon for a routine checkup. One question led to another, a stethoscope check led to an EKG, and the data was alarming enough that they operated on Monday morning.

He’s recovering just fine with his transplanted cardiac arteries, and I felt like I should pay attention to a less-than-subtle message about risk factors.

Coronary Artery Calcium Scores

Since I’d seemed willing to spend money on more tests, my family doctor offered: “We can consider obtaining a coronary CT scan for further risk stratification if you wish.”

A coronary artery calcium score? A direct examination for any evidence of possible cardiovascular disease instead of a bunch of statistics and other obscure cholesterol numbers? Detecting the calcium in the “bad” cholesterol that might be clogging my cardiac arteries?

I’m a nuclear-trained engineer and an experienced investor. Sign me up for that due diligence.

I’ve had X-rays plenty of times, and I’ve had several CT scans & MRIs. Those were all outpatient, and I thought that once again I’d simply walk into a room to stand in front of a screen for 20 minutes and share sea stories with a radiology tech while they got the pictures of my chest.

Um, no. This was still an outpatient procedure at our local hospital, yet it came with a “free” option for inpatient observation if they found serious problems. I got to meet a few of the patients before it was my turn for the test.

If you’re dealing with medical issues and possibly feeling sorry for yourself, then hanging around in the imagery waiting room will quickly recalibrate your attitude into gratitude.

A CAC exam is a series of X-ray images, but they have to work around your heartbeat. While you’re lying inside the scanning cylinder, the software synchronizes the shots to the few milliseconds between heartbeats when your heart has (briefly!) paused. The less your heart moves, and the slower it beats– to a certain point– the sharper the scan. The multiple shots are assembled into a 3D image for further analysis.

There was preparation. I could eat before the exam, but no caffeine because of the effects on heartbeat and blood pressure. They preferred that I show up well-rested and without being still amped up from surfing the dawn patrol. Ideally I wouldn’t have to drive through rush-hour traffic or be under any other stress before the exam. The hospital even has free parking.

Because of the issues with slowing down your heart for a better picture (and perhaps because most candidates for coronary scans are already having cardiac issues) I had a whole team waiting to hear my sea stories.

For those who aren’t familiar with the process, I upgraded to the CT scan with an iodine contrast. The techs poked the IV needle into my arm, injected the contrast solution, spent about 15 minutes fussing over the hardware setup, and did the first set of scans while monitoring my blood pressure. (Apparently people get pretty upset in the machine with a combination of white coat syndrome and claustrophobia. Submarine veterans… might snooze for a bit.) After consulting with the duty doctor, they woke me up decided my blood pressure was good enough (115/60) to administer a nitroglycerin tablet (under my tongue) to dilate my blood vessels. That dropped my BP down to 106/53 with a pulse of 52.

Nitroglycerin dilation feels like a nice buzz at first. Then you remember why you’re buzzing.

After the data was gathered (and once the nitroglycerin had abated) I was thanked for my service and sent home to wait for the final score. The lower, the better. “Zero” is an ideal CAC score.

I logged a 194.

That’s… not terrible… but it’s definitely not good. Cardiologists typically view scores of 100-400 as “moderate calcification.” The radiologist found “mild non-obstructive coronary artery disease” and “mildly calcified plaque resulting in minimal stenosis of the left anterior descending artery.” My arteries are still a little rubbery, but one part might be crackling with brittleness. If this is considered “mild” and “minimal”, then I’d hate to see them when they’re alarming.

The scan also showed no blood clots and no valve degeneration. (This was how I learned that the scan can detect blood clots and leaky valves.) I guess those are detectable by other means, too, but I don’t want to find out about that either.

There’s tons of research data on coronary artery calcium scores, and the important part is their long-term trend. Mine is possibly “normal for a man of my age”, but my trend is heading in the wrong direction. Or, as my family doc wrote, “You do have some narrowing of your main coronary artery […] which places you at moderate risk for future cardiac events. I recommend that we lower your cholesterol to mitigate risk of progression.”

Shopping For Statins

Now that we had direct evidence of my cholesterol damage (darn it) I shared more discussions about statins on Internet forums and asked a bunch of questions.

Again, one of my concerns rose out of Attia’s “Outlive” book: my family history of dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease (chapter 9).

Very briefly, the body gets cholesterol from three places. One source is ready-to-use cholesterol in the foods we eat, and the second is the liver synthesizing even more of it. A third source, still controversial, is the brain synthesizing its own cholesterol for its operations. There’s a theory that the brain needs a certain level of desmosterol precursor to sustain its cholesterol production… and to maintain our cognition.

(Yeah, I know. [Insert joke here about submarine XOs wondering whether I had any cognition in the first place.])

We can control some of our cholesterol by… not eating it. (“A diet high in plants and fiber.”) After that, statins of many varieties (and doses) do a great job of interfering with the liver’s cholesterol production.

However Dr. Attia (and others) are a tad concerned about interfering with the brain’s cholesterol production. The cognitive research still has conflicting data, but some types of statins can cross the blood-brain barrier to interfere with cholesterol synthesis. If I have concerns about cognition, I should avoid those types of statins. The solution might lie in using hydrophilic statins that don’t cross into the brain and thus do not mess with its desmosterol levels.

How do we monitor desmosterol levels? Well, that’s yet another blood test. I’m beginning to feel like vampire bait.

When I reconvened with my family doc to discuss prescriptions, I asked whether it was worth the time & money to get a baseline level of my desmosterol before starting a statin. He stared back blankly, so I gave him a two-paragraph printout that clarified Attia’s comments on cholesterol synthesis.

The doc was clearly dragging some memories out of cold storage from medical school, and we both agree that Attia is already a tough read. He finally said “I’ll have to take a look at this”, which is a very gratifying comment that I almost never hear from a doctor.

A few days later he e-mailed that the desmosterol research had not yet justified the cost of a test, even if the analysis was available from an Oahu lab. Only one Oahu cardiologist offers the test, but only for their patients– no a la carte pricing. Their gatekeepers wouldn’t even return my phone calls, let alone sample my blood if I drove over there with a stack of $20 bills.

I eventually found the EmpowerDX service (in Ohio) who sent a sample kit to Oahu for a refrigerated FedEx shipment to Boston Heart Diagnostics. (Which turned out to be the same lab the Oahu cardiologist uses.) If the sample’s done right (with about five drops of blood from a finger stick), and shipped correctly, then in a couple weeks you get a desmosterol level from EmpowerDX’s website.

$99 per kit. Having the financial resilience: priceless.

Contact me if you want more details on the Empower process, but it was relatively straightforward.

My desmosterol level was in spec at 1.5mg/L. (Finally, a *good* number for cholesterol!) Now that we had a statin-free baseline, I was ready to go shopping for statin choices.

My 1990s fears of side effects turned out to be overblown. Almost nobody worries about them anymore. They affect very few people, it’s almost always muscle pains (leg cramps), and the cramps appear either “very quickly” or “never” so the response is simple. The solution is switching to another type of statin or to more exotic (expensive) medications with different cholesterol-inhibiting effects.

After more discussion, we chose the entry-level hydrophilic rosuvastatin (Crestor) in the tiniest possible 5mg dose. That should start blocking my liver’s cholesterol production within a couple weeks. It won’t clear the sludge out of my cardiac artery, but ideally it’ll cut the delivery of more sludge.

A 90-day supply from our local pharmacy is a Tricare Select copay of $1.67. (Yes, less than two bucks. Hyperlipidemia is a huge national crisis and a big industry.) I can probably also get a free prescription from the VA, and it eventually shifts to mail-order refills.

The most important part of rosuvastatin? Remembering to take it regularly. I do it with my evening routine.

After a few weeks I’ve had zero side effects, and that means I probably won’t ever have them. Presumably my liver’s already slowed its cholesterol production.

I have another lipid screening with my doctor soon, and I’ll update this post.

Your Call To Action

In my 20s and 30s, I thought my annual cholesterol checks were a waste of my time. The person I am in my 60s wishes I’d paid more attention. The good news is that I’ve (finally) learned enough to minimize further damage.

Make sure you file your VA disability claim while you’re separating from the service and your memories are relatively recent. (And while the documents are on file!) Yes it’s hard to start on this with everything else happening in your life, and it gets a lot harder if you wait until you’re separated. Don’t get stuck in the Fog Of Work. Even worse (as I’ve learned), you never know when you’ll need to update the claim later.

Try not to repeat my mistakes– you’ll have more chances to live longer.

There are no affiliate links or paid ads in this post. Try your military base library or local public library before you pay money for these books– in any format.

Military Financial Independence on Amazon:

|

Raising Your Money-Savvy Family on Amazon:

|

Related articles:

Medical Tourism at Bangkok’s Bumrungrad Hospital (2025 update)

Military families: hearing aids

Why You File Your Veterans Disability Claim (Not Just How)

What Happens When (Not Just How) You File Your VA Disability Claim

What The VA Really Does With Your Disability Claim

What Happens After Your VA Disability Claim Has Been Approved

Updated VA disability claim and medical tests

Sea Story: Standing Duty During A Volcanic Eruption With A Typhoon

Lifestyles In Financial Independence: Your Mortality