Are you ready to launch into your new financially-independent life, but nervous about how the money’s going to work out?

You’re not alone. I’m getting a lot of questions about Sequence Of Returns Risk.

People are familiar with the 4% Safe Withdrawal Rate, yet we all worry about its potential failures. “Safe” isn’t enough reassurance whenever there have been failures. We humans will still obsess over a single failure even after 99 consecutive successes.

I wrote about this issue a decade ago, and now we’ll add more nuance to the discussion. Bill Bengen, the creator of what became the 4% SWR, has even more reassuring news that I’ve appended to the end of this post.

A reader writes:

“Nords, will you please remind me again?

If today is the start of my financial independence, and:

– my retirement account is invested 100% in stocks, and

– 4% is $100K which is equal to my my annual expenses in retirement, and

– I want to keep two years of expenses in cash to guard against Sequence Of Returns Risk, and

– I have little to no cash in savings and no Social Security yet,… how much do I withdraw today? $300K?”

Believe it or not, this question is common among all levels of wealth. It comes from young veterans living on their VA disability compensation or military pensions (with very little savings), and it comes from multi-millionaires in their 50s who are concerned (wrongly or rightly) about making those millions last for the rest of their lives.

For example, a surprising number of these issues come up on the Millionaire Money Mentors forum. In general, we members are very good at building wealth by earning, or saving, or investing. For some in the group, earning is a superpower… and the fear of losing that money is kryptonite to their financial independence.

Some of the forum’s higher-earning members might not be particularly skilled at saving or investing, and they’ve never been frugal. (In their strong defense, as long as they keep earning they don’t need to optimize those other skills.) Wealth builds very quickly when your annual income is $400K-$750K and your spending is $100K/year. The savings rate takes care of itself, and the investing toward financial independence can have a lower growth rate because the annual contributions are so high.

Meanwhile my spouse and I have been FI for over two decades, and I still read all of the financial research. With our inflation-fighting military pensions, VA disability compensation, and cheap healthcare, our wealth has become self-perpetuating for the rest of our lives. How did we stay FI without starting at multiple millions of dollars?!? How long can our dynastic wealth propagate among our descendants?

Even when people become millionaires from accumulation, we’re still human. We all have the same questions (and fears) about spending our wealth in a sustainable manner.

The emotions of behavioral financial psychology seem to be even stronger at a high net worth, perhaps because many millionaires found it relatively easier to earn their wealth than to preserve it. (“Easy come, easy go”…?) We don’t have to feel sorry for people with a high net worth, but everyone struggles with the concept of “enough.”

If your workplace is not stressing you mentally or emotionally, and your body can handle your avocation, then why would you want to stop? Nothing’s compelling you to quit.

If your work is challenging & fulfilling, and people are emptying dumpsters of money into your checking account, then Just One More Year is very appealing.

When you find it easy to trade life energy for money (because you’re good at earning it), then it’s scary to stop at $5M net worth because “we have to make this money last for the rest of our lives!” And besides “… we want to travel without feeling poor.”

Conceptual Errors:

Before we dive into the details of a two-year cash stash, let’s avoid the common misunderstandings.

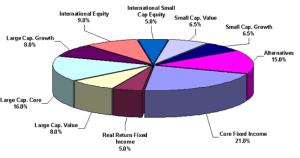

First, this tactic means that you’re easing into your financial independence with a (slightly) more conservative asset allocation. You’ve guarding against SORR with an asset allocation of two years’ expenses in cash. For example, that reduces your asset allocation (before FI) from 100% equities to (starting FI) 92% stocks and 8% cash.

We don’t know how long you’ll want to do this, but researchers estimate 10-15 years. At the end of that time, your investments would have grown faster than inflation while your spending (at the 4% Safe Withdrawal Rate) has grown with inflation. The net result of the investment compounding means that around 8-10 years into your FI lifestyle with the 4% SWR, your actual withdrawals for that coming year will be lower than 4%.

If your withdrawal rate drops below 4% (because your investments grew faster) then you’ve avoided SORR during the 30-year timeframe of the 4% SWR.

For some of us, that 30 years is longer than our life expectancy. For others, if you’re eligible for Social Security then you’ll never run out of money.

Second, this cash tactic is not intended to last longer than a recession.

It’s only two years’ expenses in cash, even if the recession lasts a few years longer. It’s intended to give your stocks a couple years of breathing room (no withdrawals) before you have to start selling some of them for your FI expenses.

You might not even sell your stocks at a loss, although a bear market (by one definition) means that you’ll sell them for at least 20% less than they were worth last year.

Third: some of your shares have grown with years of unrealized capital gains. Now you can sell older shares (with more capital gains) offset by selling the newer shares you bought just before reaching FI (which might have capital losses). You’ve sold in a tax-efficient manner and your income taxes are lower, which means you’re already reducing your FI expenses.

Fourth (This is a big one.): Humans are not spending robots.

When you’re looking at your account balances during an emotionally grinding bear market, you’re inevitably tempted to reduce or delay some discretionary spending.

Math & logic says the 4% SWR will recover from the losses. But until that happens, it’s perfectly fine to reduce expenses if it makes you feel better and helps you sleep at night.

Fifth and finally, you’re deliberately holding this cash stash in a checking account, money-market account, or high-yield savings account. The yields on these accounts mostly suck (and lose a little each year to inflation), which is the penalty we pay for having totally liquid assets.

It’s tempting to chase the yield on these by trawling the Internet for high-paying CDs or even short-term bond funds.

Please don’t chase yield. It hurts to watch this money earning next to nothing (and lagging inflation), but it’s short-term money. Lower yields (on less than 8% of your investments) will not significantly hurt your overall returns. Especially if that low-yielding cash is the first asset you spend each year.

If you feel compelled to waste your time tinkering at the margins by chasing yield, you could try to ladder some of that second year of cash in three-year CDs or even TIPS. This creates feel-good taking-action endorphins, and the early-redemption penalties for breaking a CD (in a bear market or recession) are smaller at terms of 1-3 years.

(Before anybody goes there, real estate is not cash: it’s an asset whose cashflow reduces your net expenses. If you have a vacancy, you have less cashflow.

And also: precious metals and cryptocurrencies are not FDIC-insured cash either.)

How “Two Years’ Expenses In Cash” Really Works

Getting back to that reader’s question: you’ve reached financial independence with an asset allocation of 100% equities. Now you plan to start your $100K/year spending with two years’ expenses in cash, so you sell $200K worth of your stocks.

(Yes, you’ll almost certainly have capital gains on those shares, and you’ll probably pay capital-gains taxes on them. This expense is part of your budget for the 4% SWR.)

You put $100K in your checking account to spend during the next 12 months. You could also put that in a high-yield savings account or in money markets.

You leave the other $100K of cash in a savings account for spending during Year #2. You’d make similar cash choices among HYSAs, MMs, or short-term CDs.

At the end of Year #1, you have $100K of cash somewhere among checking accounts, HYSAs, MMs, and CDs. Now it’s time to start Year #2 of your FI.

If the stock market is up for Year #1 then you’d replenish your two years’ expenses.

(Yes, “up” means at least +0.01%. Don’t over-think this part.)

Recall that the 4% SWR only withdraws 4% during the first year. After that, the heuristic means that you raise each subsequent year’s withdrawal by the previous year’s inflation. You can use any reasonable source for that number, and the standard rate of inflation is the Consumer Price Index from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

(Again, even if you’re one of my fellow submariners: don’t over-think it.)

If inflation was 3% during Year #1 then you’d cash out enough stocks to have a total of $206K cash (= [ 2 x $100K x (1 + .03)]) for the next two years. You’d put $103K in your checking account (for spending during Year #2) and leave the other $103K in your savings account.

If the stock market was down at the end of Year #1 then you’d leave your stocks alone and keep spending your remainder of the cash stash during Year #2.

If the stock market is up at the end of Year #2 from the beginning of that year, then you replenish your fund of two years’ expenses. You’ve had two years of inflation now, so you’d cash out 2 x $100K x (1+.03)^2… or whatever the CPI was during those two years.

If the stock market is down still more at the end of Year #2 (and now you’re out of cash) then you grit your teeth and sell enough stocks for one more year of expenses.

If the stock market is down yet even more again at the end of Year #3 then you sell enough stocks (again) for one more year of expenses.

In this example, by the end of Year #3 we’re in a record-breaking recession. You’d be tempted to introduce variable spending by either cutting expenses or earning part-time income. You’d cheer yourself up by remembering that your cash stash gave your stocks two years to avoid the worst of the recession before you had to sell some of them, so you’ll probably pull through anyway.

If the stock market is up at the end of Year #3 from the beginning of that year (or up at the end of Year #4, or whenever) then you replenish your two-year cash stash by selling stocks. Since you depleted your cash stash earlier and currently have zero cash, you reload your stash by selling enough stocks to support the next two years of your expenses.

Thanks, Nords, But Sheesh– How Long Do We Keep This Up?

Again, we don’t know precisely how long you’ll do this, but it’s typically (80% of history) for a decade. It’ll be closer to 10 years than 15.

By the beginning of Year #11, your investments would have grown faster than inflation while your spending (at the 4% SWR) has grown with inflation. This is likely even if you’ve just survived your first recession of your FI.

The net result of the investment compounding means that your actual withdrawals for that coming year— the amount of the 4% SWR withdrawal for that year divided by your latest net worth– would be lower than 4%.

Any inflation-adjusted annual withdrawal rate below 4% is going to last for longer than 30 years… and at 3.5% it’s highly likely to last for at least 60 years. This is reassuring if you’re in your 20s, and for everyone else it’s an estate-planning challenge in dynastic wealth.

Before you math majors (and submarine engineers) pipe up, here’s another issue: if 3.5% is going to last for at least 60 years, then why is financial independence at 4%? Why not keep working for a little while longer, like, for example, say, “just one more year”?

Because you’re working too long to end up with too much money.

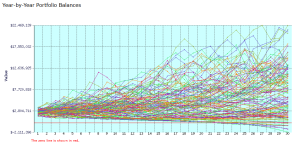

Look at the FIRECalc graphic at the top of this post, and see how many of those 124 runs end up with multimillions.

Let that sink in for a while. Millionaires have trouble with this idea too.

4% is “enough” for your self-determined expenses, and during the next 10-20 years it’ll compound to “more than enough.”

If you keep working beyond the 4% SWR tripwire then you’re trading life energy (which you might not have) for more assets (that you definitely will not need).

The *only* failure mode of the 4% SWR is Sequence Of Returns Risk. That *only* happens with 4-5 years of high inflation, or from an unprecedented decade of stock-market losses accompanied by robotic spending.

Instead of working another decade to get to a 60-year SWR, you have enough at the tripwire of the 4% SWR. While the two-year cash stash helps you avoid SORR during your first decade, the growth of your investments will take care of making your wealth last for the rest of your life.

Once you reach your financial independence, feel free to keep working if you find it challenging & fulfilling. However you won’t need the money, and you never know how much time you have left.

If I was in your situation (even in my 20s), then I’d start exploring all of my interests– and I’d cut back from full-time work.

Side Notes:

1. William Bengen, the original researcher of the 4% Safe Withdrawal Rate, knew that stocks would recover their value after a bear market or a recession. He later determined that the most common failures of the 4% SWR are caused by 6-7 years of high inflation.

(That link is cued up to the part of the video discussing the risk of 4-5 years of inflation at 6%-8%.)

2. Some of you math majors (and submarine engineers) will notice that you’re entering Year #2 with $100K (plus a little interest) but inflation has pushed your expenses up to $103K/year, so now you run out of cash in late December of Year #2. The answers to this math are:

– rounding error, don’t worry about it, or

– lumpy expenses, you probably weren’t going to run out anyway, or

– if this keeps you awake at night then do your own math for your version of “two years of expenses.” That could be something like “three-year rolling compounded average inflation of 2%-3%/year.”

3. If your asset allocation is less than 100% equities, this technique works all the way down to 60% equities and 40% bonds. Create your initial cash stash by selling some of your bonds, and feel free to keep spending the bonds after the cash is gone. See the links to a related post (below) about a rising equity glidepath.

Your Call To Action

If you’re within five years of declaring your financial independence, you have plenty of time to get ready for Sequence Of Returns Risk. It’s also the right time to think about your new life after FI.

Role-play your feelings now for your first FI bear market or recession. How will you feel when the market drops 10% in a month? 25% in a quarter? You’ll probably stop watching the financial media, but how will you feel about your dwindling cash stash?

Write down your plan for getting through the next decade of bear markets and recessions. Run retirement simulations and even build your own spreadsheets if it helps boost your confidence. You’ll refer to these records as soon as the markets drop 10%, and you’ll feel reassured about staying with your asset allocation.

There are no affiliate links or paid ads in this post. Try your military base library or local public library before you pay money for these books– in any format.

Military Financial Independence on Amazon:

|

Raising Your Money-Savvy Family on Amazon:

|

Related articles:

“OMG What If The 4% Safe Withdrawal Rate Fails?!?”

“Can a Rising Equity Glidepath Save the 4% Safe Withdrawal Rate Over a 60 Year Retirement?”

What Everyone Gets Wrong About the 4% Rule | Bill Bengen, Father of the 4 Percent Rule

How Should I Invest During Retirement?

Thanks for all that you do Doug to help the FI community with your sage wisdom and advice over the years.

You’re welcome, Mike, I enjoy paying it forward!